|

|

Reprinted from the premiere issue of HorrorShow Magazine.

Ask Doug to point out his proudest achievement, though, and it would be without question the support he has received from his friend, idol, and mentor-FX legend Dick Smith. In this HorrorShow exclusive, Doug talks about masks, monsters, and the future of FX in the horror movie industry... HorrorShow: Doug, take me back to the beginning. How did it all get started for you?

It was also around this time that I first discovered Creature Features on late night TV along with all the Universal Monster classics. I feasted on a steady diet of all those wonderfully schlocky "B" movies from the '50s and '60s, and it was right about then that I also stumbled upon what was without question the "holy bible" of horror at that time-Famous Monsters of Filmland. Needless to say, my life has never been the same after that. Literally everything I needed to know was right there in those aromatic pages; most importantly, not just the names of those who created these awesome creatures, but also how they did it! Long story short, I devoured every page, and then I started to try and duplicate what I saw in the magazine (as close as I could on a l0-year-old's allowance, that is). Then I started going to the library to pick up every book on the "3Ms"-monsters, makeup, and mold making. Naturally, that's when I started to make my own Halloween masks. HS: Which artists have served as your biggest inspirations over the years?

Bob Burns is also someone who is responsible for what I do today. His "Tracy the Ape" character from the original Ghostbusters TV show on Saturday mornings always got my attention. Then those Halloween shows of his, as well as his collection of props, costumes, and such-Bob's my hero! And I can't forget the incomparable Uncle Forry (Forrest J. Ackerman). Without his magazine, I don't know what I'd be doing now. He practically raised and educated an entire nation of horror fans with Famous Monsters. The thing is, as a kid, I didn't have the usual "heroes" like baseball or football players. My heroes were guys like Bob and Forry, people I looked up to and who I'm happy and proud to have had the opportunity to meet and become friends with. I would think that most folks wouldn't be able to say the same thing about their heroes. Also, I can't leave out Mom and Dad. They practically allowed me to wreck their basement in my early years trying to figure this stuff out, and their encouragement and support of my "hobby" was invaluable. HS: Walk me through the process of how you make one of your masks.

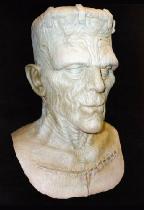

Basically, though, I usually start with an armature (a lifecast or pipe-and-wire armature) and apply my clay to that, using my hands to get a rough idea of the look and size I want. Then I refine the sculpt even further with a variety of tools (wire loops, rakes, brushes, texture pads) until I arrive at the finished sculpt. Then it's time to make a two-piece "plaster" (usually Ultracal 30 or Hydrocal) mold of the sculpt, which to me is the really fun part. Once the mold is finished, the two mold halves are carefully separated, the clay is cleaned out, the two halves are strapped tightly together, and the latex is carefully poured in (watch those air bubbles) and left to sit for about two hours. After that happens, the latex is then poured out, and the mold is left to drain a bit more, then it is left to dry overnight. The next day it will be completely dry. Then, after powdering the inside of the casting to prevent sticking, we carefully peel out the latex "skin"-the mask. After a little more drying time, a bit of trimming is necessary, and it's ready to be painted, usually with an airbrush. A little hair, blood, extra gore, and presto-a finished mask! That's pretty much about it in a nutshell.

DG: My studio is actually a converted two-story warehouse unit that I stumbled into some years ago. The basement just couldn't hold any more stuff, and I needed more space. It's about 1,000 square feet, and it allows me to take on larger projects that I couldn't do before due to the lack of room. Lots and lots of work space, which means bigger, better creatures. I can just about accommodate anything short of Jurassic Park kind of stuff, but my main bread-and-butter are masks and props at the moment, along with some film work in Chicago. HS: When you first started making masks of your own, how did you proceed? DG: Well, I started out just doing some really crude half faced masks sculpted over a styrofoam wig block — nothing earth shattering, but it was a start. I tried to duplicate some things I saw in movies and such, but again, my lack of sculpting ability and knowledge of anatomy made for some pretty lousy masks. But hey, I was a kid, and with each "failure" I tried that much harder the next time. I started to go to the local library, checking out books on anatomy, as well as devouring every bit of information I could out of Famous Monsters, Fangoria, and Cinefantastique. The best ones, though, were Gorezone and Cinefex — such a wealth of information in those pages for beginning FX artists and mask makers. Great reference photos, interviews ... everything was explained and "secrets" were then unlocked. After that, my work improved tremendously, and then I started to branch out into doing my own, original stuff after years of copying the classics. HS: When did you start selling your masks? What was it like to make that transition, from making them for your own enjoyment to doing it professionally?

A friend of mine then came over to my basement "studio" with a magazine with an ad from a company called "Death Studios" showing some of the coolest masks I had ever seen. We then found out that they were located only an hour or so away from where I lived, so I nervously called them for a catalog, and asked a few questions, which they kindly answered. After seeing the quality of their stuff, it made me try even harder. Then I was doing a mask of a cartoon character that my friend John Ramirez came up with ("Danny the Bastard"). When it was done, I figured I'd send a photo to Death Studios, and see what they thought, just to get an idea of how I was progressing. A few days later, they were on the phone, asking me if I'd be interested in having my mask in their lineup! I couldn't believe it — the top, most respected mask company wants my work! I was on cloud nine for days. After that, my confidence level went up, and I started taking things a bit more seriously. Over the next few years and a few more masks for Death Studios, I went more into the FX stuff, trying to build up a portfolio, and trying to break into that business. I then sent some photos to my "hero" Dick Smith. I wanted to take his makeup course, as it was the most respected and highly recommended course/school in the field. Dick doesn't like anyone who applies-you have to show him some really professional work to be accepted. So I gathered up photos of what I thought was my best work, wrote a nice letter, packaged everything up, and went straight to the post office. That had 10 be the longest week of my life after that. Then, early that next week, I got a letter — it was from Dick Smith. I have to tell you, I was afraid to open it right away. Every bad thought went through my mind: I didn't get accepted, I'm not good enough, etc. Then I opened it. Bar none, it was the most wonderful letter I’ve ever received. Dick not only warmly welcomed me into his course, but he said he really liked what he saw and that I was more than qualified to join. Life was never the same after I hat. HS: Given your love of the classic monsters, what do you think of today's mainstream horror films? DG: I'm a big fan of the classics. They are what I grew lip with and was raised on. Today's monsters probably won't be remembered that well over the test of time. While today's artists are incredibly talented and have unlimited resources to produce the most realistic things we have ever seen, a lot of stuff is just another "version" of what's already been done (and done well). Today's audiences are bombarded with endless sequels, rip-offs, and remakes-nothing really that original, in my opinion. The new "horror" icons have been so watered down, and you can blame the studios for that. They are only interested in the money, so they always play it safe. My opinion has HS: What is your opinion on the increased use of CGI in films, and do YOLI think it will eventually displace traditional makeup and PX? DG: In my opinion, CGI is a very valuable tool, but like anything, it's only effective if used properly and is well-done. Producers now think they can do everything on a computer. Ever see some of this stuff nowadays? It's a joke. The FX stand out so badly — it's completely obvious! Does anybody actually think this stuff is good? On the contrary, films like Jurassic Park are examples of how to do it correctly. They used CGI for scenes where it was completely impossible to use live-action animatronics. They also used the dark of night and the rain to hide some of the imperfections too. Then for the close-up interactions with the dinosaurs with the actors, that's when the animatronics came in. The actors and the creatures were sharing the same light and scenery, making it more believable. Now, eventually computer technology will get to the point it probably will take over completely, but I can't see that happening for a while. Right now the perfect idea is to blend both. A lot of the computer guys aren't skilled enough as artists to capture the look, color, and movement that live-action, traditional artists can capture in their work. Look at Phil Tippett on Jurassic Park. The filmmakers had all that technology and software, but it took an old school stop-motion expert to show and teach them all the subtleties of movement, colors, and such. That's why a lot of makeup FX guys are being lured into CGI by various studios. It's getting better, but it's still being overused or used at the wrong times. The most memorable and scary movies of all time used traditional, old school techniques, with a lot of imagination and creativity. That's what's being forgotten. HS: For the Advanced Course, what are the requirements that need to be fulfilled before earning the certificate? How much time would this process take, on average?

He wants all of us to take what he teaches us, and try to take it beyond. Consistent, professional level work that shows this is awarded his certificate. As far as a timeframe, there is none that I know of, or that has been mentioned. When you're ready, Dick will let you know. Some folks have completed his course in a year or so; some a lot longer. It's all up to the individual and how much time they can devote to the course. Even seasoned, working professionals who are already established are still taking it and are working towards that certificate. Like I said, it's the holy grail for F/X artists. |

|||||||

All content © 2009 Doug Goins / Hoosier Effects Lab, Ltd. | Website by Imagehaus Creative |

||

|

|

always been that cool, memorable monsters aren't supposed to be safe.

always been that cool, memorable monsters aren't supposed to be safe.